Science in Islam

Science in IslamIslamic science was in its prime during the European Middle Ages, between the 9th and the 13th centuries, particularly in the brilliant period of the Abbasid caliphate from the 9th century to the 11th. A considerable degree of education and scientific knowledge existed on many levels of Islamic society. At the time of the Crusades, for instance, the Islamic knights could read and write, skills which were exceptional among their Western opponents. H

owever, the encouragement of science and art was mainly the province of the courts, from the caliphate in Baghdad down to the residences of local governors and minor regional potentates. Many a second-tiered ruler made his court an important center of science and art, the best example being the Spanish taifa rulers of the 11th century. All the major philosophers and scientists of the Islamic world spent at least some time at such a court. They not only received money from open-minded and interested rulers, but were often appointed as their political advisers.

owever, the encouragement of science and art was mainly the province of the courts, from the caliphate in Baghdad down to the residences of local governors and minor regional potentates. Many a second-tiered ruler made his court an important center of science and art, the best example being the Spanish taifa rulers of the 11th century. All the major philosophers and scientists of the Islamic world spent at least some time at such a court. They not only received money from open-minded and interested rulers, but were often appointed as their political advisers.The sciences of Islam, particularly the so- called exact or natural sciences in the widest sense, had from time immemorial taken as their unquestioned authorities (together with the religious sources of the Koran and the Hadiths) the writers of Greek antiquity, more particularly the philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, to whom every scientist referred in one way or another. Another authority was the physician Galen. Contrary to what is generally thought in the West, where the achievements of Arab and Persian science are seen as consisting almost exclusively in the preservation and transmission of the inheritance of classical antiquity, these scholars adopted an intellectually original and independent approach to the texts of antiquity; the Greek inheritance was not simply copied and read, but revised, brought into line with the requirements of Islamic culture (and religion), supplemented, and expanded.

A striking feature is the universal erudition of Islamic scientists. The thinkers of the early period were almost all trained physicians and recognized medical authorities. They were also skilled astronomers, and developed complex philosophical systems based largely on the natural sciences, but they also tried to reconcile and interrelate religion and science, not a contradiction in terms in the Islamic concept of reason. Many of them also produced travel writings and autobiographies, and experimented with alchemy, particularly in the manufacturing of precious metals. In each of these areas they wrote a great deal and compiled extensive collections, taught students, gave lectures,and enriched the libraries of their princely patrons. Many scientific terms and names of plants and spices reached the European languages by way of Arabic or Persian. These words include alchemy, algebra, alcohol, amulet, caliber, carat, chemistry, cipher, elixir, magazine, mummy, sugar, talisman, and zenith. Expansion of the trade and travel routes of the Islamic world also ensured the extensive distribution of scholarship and written works.

Philosophy and the caliph’s dream

Philosophy and all the other sciences received their first major boost under the scholarly Caliph al-Mamun (813—833) and his direct successors. Al-Mamun made the rationalistic faith of the Mutazilites the state religion, allowing philosophy to free itself from its subservience to theology. This encouraged an interest in the thinking of classical antiquity by announcing that a dignified old man had appeared to him in a dream, identified himself as Aristotle, and that he had expounded the nature of good on a basis of philosophical doctrine (rather than divine revelation).The first major philosopher of Islam was al-Kindi (c. 800—870), a descendant of a distinguished family, who took Platonic thinking as his point of departure, argued for the acceptance of causality, and also wrote over 200 works on subjects ranging from philosophy, medicine, mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy, and music. He was also politically influential as the tutor of princes at the court of Caliph al-Mutasim, where he introduced arithmetic using Indian numerals. Al-Farabi (C. 870—950), who bore the honorific title of ”second teacher” (that is to say, second only to Aristotle) and was active at the court of the Hamdanids of Aleppo, combined Aristotelian thinking with neo-Platonism, and confidently stated that philosophy held the primacy over theology. In his book, The Model State, he sets out the pattern of an ethical and rational ideal state, ruled by a philosopher king who also has some of the characteristics of an Islamic prophet.

One of the most important Islamic polymaths was lbn Sina of Bukhara (C. 980—1037), known in the West as Avicenna. He worked to compile a detailed collection of all the knowledge of his time, wrote works on philosophy, astronomy, grammar, and poetry, and was regarded as one of the most outstanding physicians of his day. He also wrote a remarkable autobiography, and held important political offices at various princely courts. In his major work, The Book of the Cure (of the Soul), he combines metaphysics and medicine with logic, physics, and mathematics. His compendium of medicine was regarded as a standard work in Europe as well as the Islamic countries until the early modern period. Avicenna’s contemporary al-Biruni (973—1048),who came by adventurous ways to the court of the Ghaznavids Mahmud and Masud, and

remained bound to it for the rest of his life in a curious love-hate relationship, proposed strong links between philosophy and astronomy in his book Gardens of Science. He accompanied Mahmud of Ghazna on Indian military campaigns, and wrote a cultural history of the Indian world.

Ibn Tufail (c. 1115—1185), who enjoyed the protection of the Almohads, was an original thinker. His work, The Living One, Son of the Watcher (God), tells the story of an Islamic Robinson Crusoe who is cast up on a desert island, where he comes to an understanding of the world and the nature of the One God through natural reason alone.

Philosophy in Islam reached its peak with lbn Rushd (c. 1126—1198), who was also under the protection of the Almohads,and became known in the West as Averroes. As an uncompromising champion of Aristotle, he supported the idea of the eternal existence of the world and the cosmos, which had no beginning; in his doctrine they were created by God, but developed according to their own laws. The intuitive mind, Aristotle’s nous, was a purely intellectual entity to Averroes, operating on the souls of men from outside, and he therefore rejected ideas of the continued existence and immortality of individual souls. He came into violent conflict with Islamic orthodoxy, had to face many tribunals and hearings, and often survived only because he enjoyed the protection of the Almohad rulers. The doctrine of the eternity of the world and its existence without beginning reached the West as “Latin Averroism” (its outstanding proponent was Siger of Brabant at the Sorbonne in Paris), and it was contested by the most important European thinker of the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas, who himself was strongly influenced by Aristotelianism of the kind proposed by Averroes. In the Islamic world, however, orthodox and dogmatic theology clearly gained the upper hand over philosophy.

The natural sciences: astronomy, physics, and medicine

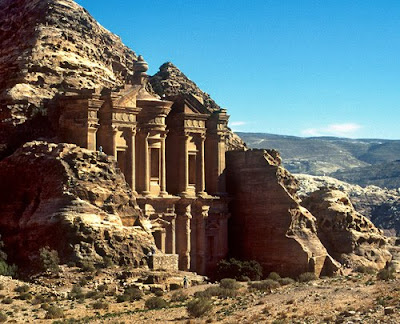

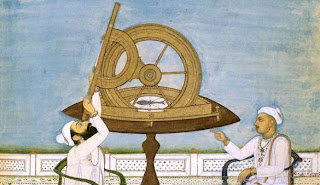

Islamic science’s special interest in astronomy was derived from the traditions inherited from old oriental religious communities, such as the Parsees, and in particular the Sabaeans of ancient Mesopotamia, whose center was in the north of Iraq and who were largely absorbed by Islam in the 11th century. Under Hellenistic influence their original Babylonian cult of the heavenly bodies had given way to monotheism, but they still retained ancient oriental knowledge of the mathematical calculation of the course of the planets. Such calculations fascinated Islamic scientists because, under Greek influence, they developed a concept of the divine architect of the universe as a great mathematician and geometrician who kept everything in order by the operation of precisely calculable laws. Astronomy and astrology were closely connected in this system of thought, and the calculation of favorable conjunctions became a politically influential field of knowledge. All the important philosophers, and many rulers, took an interest in astronomy, calculated the courses of the stars and the dimensions of the earth, forecast the weather, and predicted the state of the water supply — calculations that served very practical purposes.

The Fatimid caliph al-Hakim, for instance, made use ofthe knowledge ofthe astronomer and physicist lbn al-Haitham or Alhazen (965—after 1040), who was required to calculate the amount of water in the Nile for agricultural purposes. Alhazen is regarded as the greatest physicist of the Middle Ages, and was outstanding for his work on optics, in which he described refractions of light in calculating the earth’s distance from the stars. Al-Biruni, mentioned above, drew up very precise measurements of the earth, constructed a great globe, and made remarkable progress in the understanding of the rotation of the earth and the force of gravity. The phenomena of solar and lunar eclipses could be very precisely calculated at this time. Many astrolabes and astronomical charts, once the property of rulers well versed in astronomy, have been preserved. Outstanding among such rulers was Ulugh Beg (1 394—1449), the grandson of Timur, whose residence was in Samarqand.ln 1428/29 he had a huge observatory built with a sextant for calculating the height of the sun, and with the aid of expert astronomers, drew up the most precise astronomical charts of the Middle Ages.

Medicine was at first very closely linked to philosophy, and every Islamic thinker who was also a doctor developed theories about mankind from both a medical and a philosophical viewpoint. Hunayn ibn lshaq (808—873), an Arab Christian, had studied with Arab and Byzantine scholars and doctors, and became the most important translator into Arabic of the medical writings of classical antiquity, particularly the works of Galen. Everywhere he went on his long journeys he collected the texts of classical authors, translated them, compared them, and then wrote commentaries on them. His meticulous methodology allowed for the compilation of a medical canon with a standardized vocabulary that became the basis of medical training in the Arab countries; he himself was an excellent eye specialist, and wrote compendia describing his own medical methods. The independent-minded Persian Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865—925),also known as Rhazes in the West, organized hospitals in Baghdad and Rayy, compiled a collection of clinical cases, and thus created a great medical encyclopedia. He communicated the knowledge that it contained in his own extensive teaching activities. He championed the liberation of medical and scientific thinking from the dogmas of religion, made many experiments in alchemy, and described the symptoms of smallpox. Interestingly, he called the philosopher Socrates the “true imam” of reason, since so far, to his way of thinking, the prophets had done nothing but sow discord among mankind.

The medical schools in the Islamic world made great progress in the fields of pharmacology, infectious disease, therapeutics, and above all the treatment of eye disorders; around the year 1000 they were already successfully operating on cataracts, and also knew a great deal about the circulation of the blood, which is shown in many illustrations. Finally, the physician lbn an-Nafis discovered pulmonary circulation through his understanding of the impermeability of the membrane of the heart. Many Islamic rulers founded large hospitals that took patients from all walks of life and nursed them around the clock. There were also special hospitals for the” care of lunatics,” with trained staff.

The compendia of lbn lshaq, Rhazes, Avicenna, and other scholars reached Europe by way of southern Italy and Andalusia. Avicenna’s Canon Medicinae, in particular, became a major textbook of Western medical schools. Arab physicians thus not only handed on the knowledge of classical antiquity, but were the direct forerunners of medical progress in Europe from the Renaissance.