The presence of art — that is to say, of techniques beautfying man’s surroundings and of the evaluation of things made or built by and for society or individuals — is generally assumed for all coltores. And in each place this art has been affected by ideological, social, religious, historical, or geographical constraints; this explains why individual civilizations have artistic traditions which differ from each other. Islamic culeore is, of course, no exception, and this chapter will elaborate on a few of these constraints.

Firstly, there are the complex ways in which Islamic culture recognized, accepted, or rejected the historical past in inherited or conquered regions. A second constraint consists of features imposed or implied by the new faith; although interpreted differently over the centuries, these are altogether permanent and constant characteristibs of Islamic civilization. The special aae of the mosque, which was not technically a requirement of the faith at its inception but which became a constantly evolving requirement and sign of Muslim presence, is a third example of a particularly Islamic development and constraint. The last two constraints that developed derived from particularly original features of Islamic culture. One is the encounter of the new faith with the ancient philosophy of classical Greece, and with the mathematics, technology, and natural sciences available in the Mediterranean world in late antiquity, in Iran, in India, and even in China. This occurred first in Baghdad, the center of Muslim thought and rule, and then expanded slowly and eventually, nearly everywhere in the region. The other is the character of the literature created in the Islamic world. Like all literatures of this time, it was meant both to edifr and to please. In the forms it developed in Iran from the 12th century onwards, it was a literature of universally effective lyricism and had a considerable impact on the arts.

Muslim thought and the literature of Muslim lands are but two of several social and cultural constraints influencing the arts: possibly the only ones which have affected the whole Muslim world. Other constraints, for instance

Firstly, there are the complex ways in which Islamic culture recognized, accepted, or rejected the historical past in inherited or conquered regions. A second constraint consists of features imposed or implied by the new faith; although interpreted differently over the centuries, these are altogether permanent and constant characteristibs of Islamic civilization. The special aae of the mosque, which was not technically a requirement of the faith at its inception but which became a constantly evolving requirement and sign of Muslim presence, is a third example of a particularly Islamic development and constraint. The last two constraints that developed derived from particularly original features of Islamic culture. One is the encounter of the new faith with the ancient philosophy of classical Greece, and with the mathematics, technology, and natural sciences available in the Mediterranean world in late antiquity, in Iran, in India, and even in China. This occurred first in Baghdad, the center of Muslim thought and rule, and then expanded slowly and eventually, nearly everywhere in the region. The other is the character of the literature created in the Islamic world. Like all literatures of this time, it was meant both to edifr and to please. In the forms it developed in Iran from the 12th century onwards, it was a literature of universally effective lyricism and had a considerable impact on the arts.

Muslim thought and the literature of Muslim lands are but two of several social and cultural constraints influencing the arts: possibly the only ones which have affected the whole Muslim world. Other constraints, for instance

Early Arabian art

Islam was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in western Arabia in the early 7th century. Later Muslim historiography defined this peri as a “time of ignorance” (the jahilsya), in the primary sense of a spiritually unenlightened period, but also as a time of relatively limited cultural achievement. This was always, however, with the exception of poetry, which became an exemplar both for its themes and for its forms. ‘Whether western Arabia was indeed at this time in a state of cultural and artistic poverty is a matter of some debate. Few artistic remains are directly connected with the area, and only the site of al-Faw in Saudi Arabia has been excavated, partly at least. Luxury and other manufactured items, such as they existed, were, for the most part, imported from elsewhere, primarily Egypt and the Mediterranean, but also India, which was much involved in the Arabian trade. Architecture was hardly present in terms of major monuments, but the societies of western Arabia, nomadic and settled, did possess spatial concepts, as illustrated by a rich vocabulary dealing with boundaries between different kinds of places and with permanent or ephemeral sacred enclosures. And the Kaaba in Mecca, which became the holiest spot in Islam, the direction (qibla) towards which all Muslims pray and the goal of the pilgrimage (haj)) is a pre-Islamic sanctuary that had been used for centuries by pagan tribes. Although occasionally modified, its basic shape was the same; before Islam, the practice of covering it with an expensive cloth accent its use as a shrine for idols and a focus for all the religions of the Arabian Peninsula.

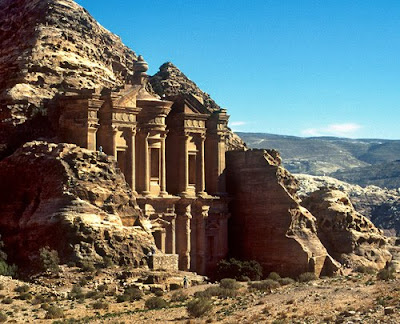

Other parts of the vast Arabian world had an often brilliant artistic history. Nor much is left of it in Yemen, except for remote temples and spectacular irrigation works used to control the flow of an often unpredictable water supply. Medieval sources often described the tall buildings of that land, and the memory of their sculpted decoration, for instance roaring lions on top of buildings, entered the realm of myth and fantasy. The most spectacular and best-known pre-Islamic Arabian cultures were those of the Nabaraeans, centered on Petra in Jordan, and of Palmyra, farther north; both are now celebrated tourist attractions.

These Arab kingdoms left a major architectural tradition, strongly influenced by Hellenistie and Roman imperial models and practices, and, especially in Palmyra, impressive sculpture in temples and, above all, neeropolises. Even though the remains of Nabataean and Palmyran art must have been even more spectacular in the Middle Ages than they are today, there is practically no acknowledgment of the existence of that art in medieval Islamic written sources and very little in artistic remains. Here and there for instance in the sculpture of the Umayyad palace of Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi in the Syrian steppe — the impact of neighboring Palmyra is clear and some have argued that certain features of early Islamic representational art — deeply drilled eyes in sculpture and lack of facial expression in paintings — should be related to the styles and techniques of these early Arabian kingdoms. But, outside of the obvious example of Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi, the relationship, while nor impossible, is difficult to demonstrate. It seems, then, proper to eunelude that the great and original Arabian cultures that developed in the north of the Arabian Peninsula, between Syria and Iraq, under the aegis of the Hellenisrie and Roman empires, were indeed barely present, if not wilfully obliterated, in the collective memory of traditional Islam.

This is not so in the instance of two tribal Arabian kingdoms, those of the Lakhmids and the Ghassanids, which flourished during the centuries before Islam in the steppe borderlands of Iraq, Syria, and Palestine, respectively. They are usually remembered for their role as client states of Byzantium and Sassanian Iran, protecting each empire from the other. However they were also significant cultural entities of their own with a considerable impact on the following centuries, if not necessarily during their flowering in the 5th and 6th centuries. The Lakhmid palace of Khawarnaq in southern Iraq remained as a monument of fabled luxury even in much later Persian poetry. The first steps towards a differentiated Arabic script took place under the aegis of the same dynasty, while the Ghassanids sponsored the construction of many building in Syria, one of which, an audience hall, still stands in Rusafa, in the northern Syrian steppe, and includes an inscription in Greek celebrating the king al-Mundhir.

Altogether, the Arabian past seems to have played a relatively small

role in the development of Islamic art, especially if forms are considered exclusively. Its importance was greater in the collective memories it created and in the Arabic vocabulary for visual identification it provided for future generations. It is, of course, true that the vast peninsula has not been as well investigated as it should be and that surprises may well await archeologists in the future. At this stage of scholarly knowledge, however, it is probably fair en say that Islam’s Arabian past, essential for understanding the faith and its practices, and the Arabic language and its literature, is not as important for the forms used by Islamic art as the immensely richer world, from the Atlantic Ocean to Central Asia. Taken over by Islam In the 7th and 8th centuries. Even later, after centuries of independent growth, new conquests in Anatolia or India continued to bring new local themes and ideas into the mainstream of Islamic art. It is only today, inline with national aspirations for traditions related to a land as much as to a culture, that interest in the pre-Islamic monuments of Arabian history has increased.

These Arab kingdoms left a major architectural tradition, strongly influenced by Hellenistie and Roman imperial models and practices, and, especially in Palmyra, impressive sculpture in temples and, above all, neeropolises. Even though the remains of Nabataean and Palmyran art must have been even more spectacular in the Middle Ages than they are today, there is practically no acknowledgment of the existence of that art in medieval Islamic written sources and very little in artistic remains. Here and there for instance in the sculpture of the Umayyad palace of Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi in the Syrian steppe — the impact of neighboring Palmyra is clear and some have argued that certain features of early Islamic representational art — deeply drilled eyes in sculpture and lack of facial expression in paintings — should be related to the styles and techniques of these early Arabian kingdoms. But, outside of the obvious example of Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi, the relationship, while nor impossible, is difficult to demonstrate. It seems, then, proper to eunelude that the great and original Arabian cultures that developed in the north of the Arabian Peninsula, between Syria and Iraq, under the aegis of the Hellenisrie and Roman empires, were indeed barely present, if not wilfully obliterated, in the collective memory of traditional Islam.

This is not so in the instance of two tribal Arabian kingdoms, those of the Lakhmids and the Ghassanids, which flourished during the centuries before Islam in the steppe borderlands of Iraq, Syria, and Palestine, respectively. They are usually remembered for their role as client states of Byzantium and Sassanian Iran, protecting each empire from the other. However they were also significant cultural entities of their own with a considerable impact on the following centuries, if not necessarily during their flowering in the 5th and 6th centuries. The Lakhmid palace of Khawarnaq in southern Iraq remained as a monument of fabled luxury even in much later Persian poetry. The first steps towards a differentiated Arabic script took place under the aegis of the same dynasty, while the Ghassanids sponsored the construction of many building in Syria, one of which, an audience hall, still stands in Rusafa, in the northern Syrian steppe, and includes an inscription in Greek celebrating the king al-Mundhir.

Altogether, the Arabian past seems to have played a relatively small

role in the development of Islamic art, especially if forms are considered exclusively. Its importance was greater in the collective memories it created and in the Arabic vocabulary for visual identification it provided for future generations. It is, of course, true that the vast peninsula has not been as well investigated as it should be and that surprises may well await archeologists in the future. At this stage of scholarly knowledge, however, it is probably fair en say that Islam’s Arabian past, essential for understanding the faith and its practices, and the Arabic language and its literature, is not as important for the forms used by Islamic art as the immensely richer world, from the Atlantic Ocean to Central Asia. Taken over by Islam In the 7th and 8th centuries. Even later, after centuries of independent growth, new conquests in Anatolia or India continued to bring new local themes and ideas into the mainstream of Islamic art. It is only today, inline with national aspirations for traditions related to a land as much as to a culture, that interest in the pre-Islamic monuments of Arabian history has increased.

The rock tombs of Petra, Jordan

The rock tombs of Petra, JordanPetra was one of the most important regions in the ancient Arabian cultural area,and from the 4th century B.C. was at the center of the old Arabian kingdom of the Nabataeans,who made it a flourishing commercial market,and controlled a large part of the”lncense Road.” They thus profited from the trade between the Greeks, Medes, Persians, and Egyptians, and set up many depositories to protect their goods. In the 2nd century b.c. they extended their rule to Syria and Palestine, but were defeated in AD. 106 by the emperor Trajan, and the area became a province of the Roman Empire. Characteristic evidence of Nabataean culture exists in the multistory temples and tombs built into the rock walls of Petra, and in Aramaic inscriptions on stones. Petra lay forgotten for a long time, and was not rediscovered by archeologists until the beginning of the tsth century.

Donate for encourage Now

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น